A Trip Back in Time: 100 Years of Cosmetic Medicine

Modern practices of cosmetic medicine can be traced back to the turn of the 20th century, but these stories and the people they are made up of are often relegated to being curious footnotes in medical history.

I want to take you on a little trip back in time, 100 years ago, to see the birth of modern cosmetic medicine in the States and the UK. You’ll read about non-medical charlatans, and some of the pioneers of this medical specialty. Of greater interest, you will see the parallels between the unregulated practice of a century ago, and the field of medical aesthetics in the UK today.

Setting the Scene

In my article Botched!, I discussed the issues with all the quacks with no medical training running rampant and causing complications to the unsuspecting public during this time period (similar to the state of affairs in the UK today!). At the time, this medical specialty was not taken seriously and was devalued by all of the harm done by non-medics and by the stigma attached to it by other clinicians.

Dr. Charles C Miller wrote a scathing piece of the state of cosmetic medicine in the early 20th century.

"Unscrupulous charlatans" and "advertisers of indifferent ability" were "reaping a harvest of dollars" and leaving in their wake "mutilations and disfigurements, which mean the lifelong distress of their unhappy victims." But surprisingly, he laid most of the blame at the feet of his fellow medical professionals, who he felt did not take the specialty seriously enough to safeguard the public, which is what allowed the non-medics to run rampant.

Unfortunately within the context of this landscape, much like today, this meant there was a huge deal of stigma attached to procedures that were undertaken for cosmetic purposes, both for those practicing and those receiving the procedures.

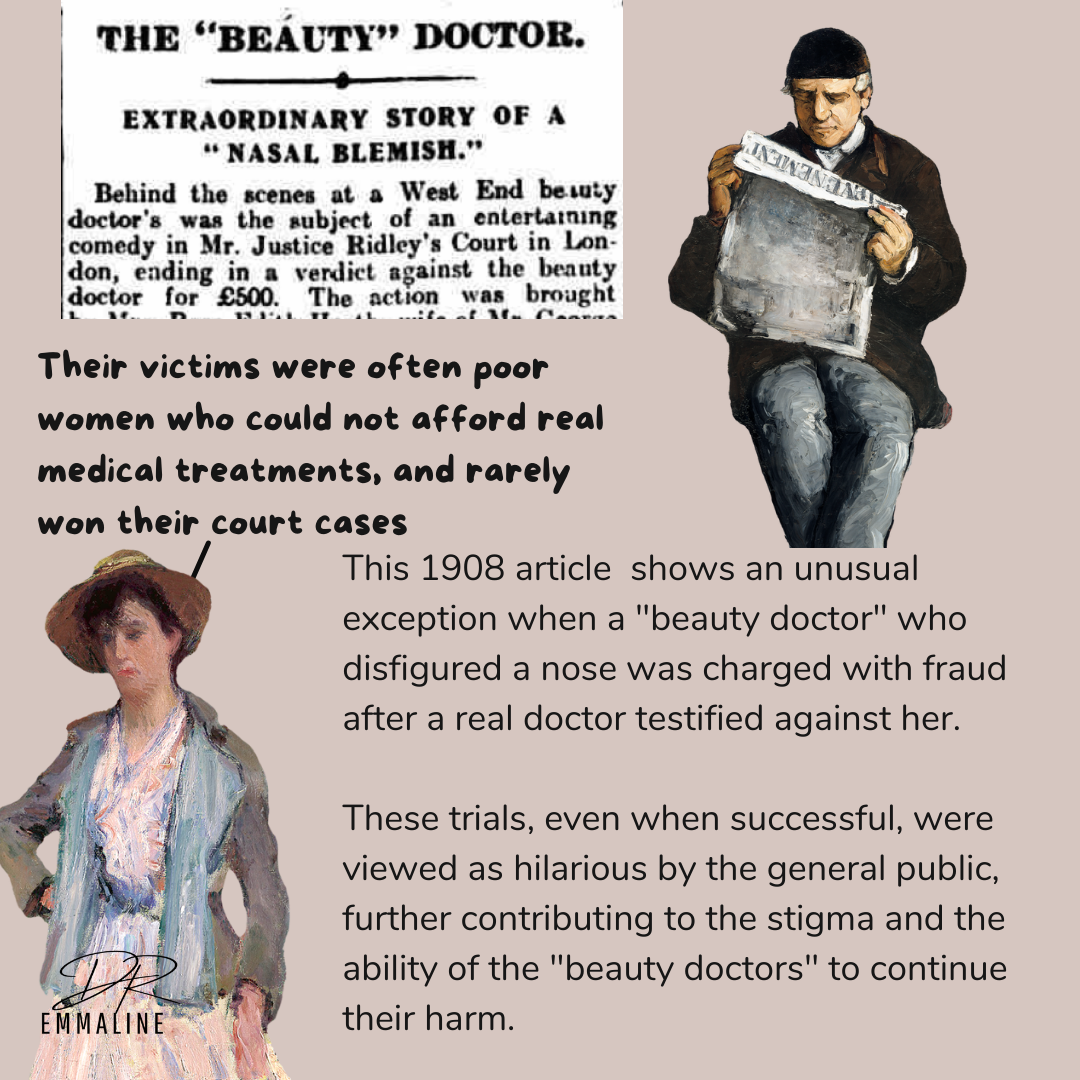

In the UK, this impression was solidified by a famous trial that took place in 1904 - the case of a “beauty doctor” (with no actual medical training) who was sued by a dressmaker for giving her a treatment that promised to make her wrinkles disappear.

Headlines shouted with glee, “The Wrinkles Came Back!” and by all accounts the courtroom was packed with spectators who found the entire episode incredibly hilarious. A long description of the various tinctures and creams put on this poor woman’s face over many days followed, with wonderful descriptions from the dressmarker about how she was made to look like “ a pudding basin” and a “half-roasted beefsteak.” Unfortunately, the overall effect of this trial was that the British public felt that cosmetic treatments, and “beauty doctors,” belonged solely in the realm of quackery.

“Featural Surgery”

Meanwhile, this sense of quackery also existed in the United States. One man was trying to change things, however he found little success.

Dr. Charles C Miller, a fascinating and important figure and arguably the father of cosmetic medicine, has often been relegated to the footnotes of history. We’ve briefly mentioned him in our history of aesthetic medicine piece, and it is undoubted that he was a controversial figure. He was a passionate advocate of cosmetic medicine as a legitimate specialty and hated the non-medics that devalued the work. Unfortunately, the stigma that surrounded cosmetic procedures meant that he was often lumped in with them.

Born in 1880, he graduated from medical school in 1899 and set up a practice in Chicago. He called his specialty “featural surgery,” a field that we would later call cosmetic medicine and plastic surgery. He began writing up case reports and publishing photographs of his work for patients, including non-surgical rhinoplasties (with paraffin) and eyelid surgeries.

He published an incredible textbook called Cosmetic Surgery: The Correction of Featural Imperfections in 1907, the entirety of which you can read here. It is a surprisingly modern and thorough text. Again, showing great foresight, he opens his book with the following statement: “A large number of the profession are at the present day apathetic regarding elective surgery for the correction of those featural imperfections which are not actual deformities but such apathy cannot pre- vent the development of this specialty as the demand for featural surgeons is too great on the part of the public.”

Much of his work dealt with what we would recognise as injectable treatments, although he did not have access to the hyaluronic acid dermal filler we do today. He used both paraffin wax as described earlier, and substances of his own creation, administering them with cannulas and needles. He later recognised the limitations of paraffin as an injectable and published a paper describing this.

However, his attitude towards his patients could be somewhat reckless, and he was plagued with legal troubles in the 1920s for operating drug stores which mishandled prescriptions. Perhaps he was frustrated at his isolation in this new exciting field, and felt his brilliance was unrecognised and unrewarded. He was completely forgotten by the next generation of plastic surgeons. Some of his medical procedures were really the first of their kind, and later surgeons would take credit (either knowingly or unknowingly) for work that Charles C. Miller pioneered.

Removing the Quacks

The medical community became determined to remove the quacks and charlatans from their midst. This was achieved by the establishment of professional governing bodies for medicine and the specialty of plastic surgery, and extensive public education to check their practitioner’s credentials before engaging in a cosmetic treatment.

But the issue continued to be a confusing one of the public. A journalist at the time wrote in the Women’s Home Companion, “On one flank are the reputable plastic surgeons and dermatologists. On the other flank is the vast and growing array of beauty shops for the most part conducted by conscientious hard-working women who confine themselves to such harmless and proper work as bobbing hair and giving facial massage… In between is a horde of charlatans. The borderline between the legitimate and the illegitimate in facial operations is very narrow and hard to define.”

There were several factors that contributed to British plastic surgeons distancing themselves from purely cosmetic treatments in the twentieth century. One of the primary factors was a desire to establish plastic surgery as a legitimate medical specialty, rather than simply as a means of improving appearance. Plastic surgeons sought to distinguish themselves from other practitioners offering cosmetic treatments, many of whom had little or no medical training, and to position themselves as experts in the reconstruction of the face and body after injury or disease.

Another factor was the high demand for plastic surgery among patients with medical needs, such as those who had suffered burns, injuries, or birth defects, particularly as the profession was born in the aftermath of the World Wars. Many plastic surgeons felt that their skills and expertise were best suited to helping these patients, rather than performing purely cosmetic procedures.

However, it is also possible that cultural attitudes and misogyny played a role in the distancing of plastic surgeons from cosmetic treatments. At the time, there was a perception that cosmetic treatments were primarily for women, and that the pursuit of beauty was frivolous or vain. This may have led some plastic surgeons (who were all male) to view cosmetic treatments as less serious or less legitimate than other areas of the field.

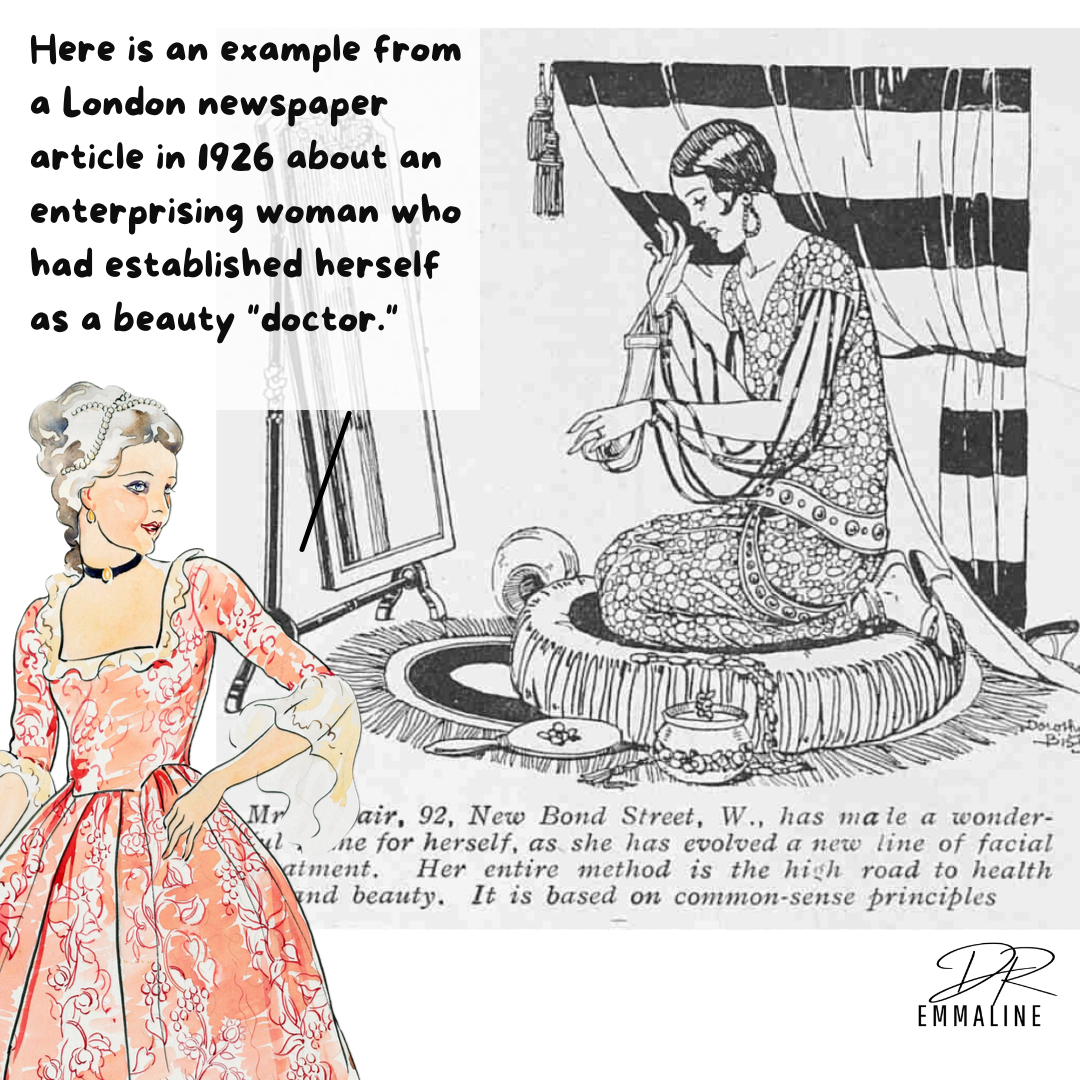

There may also have been a bias against women in the medical profession, which made it difficult for female plastic surgeons or other women practitioners to be taken seriously in the field. This may have contributed to a sense that cosmetic treatments were less important or less deserving of attention than other areas of plastic surgery. It is worth noting that many of the female “beauty doctors,” like Anna Ruppert, would not have had the opportunity to go to medical school even if they wished to do so.

Steps Forward

However, there were some positive steps being taken as more and more clinicians were recognising the importance and benefit of cosmetic procedures.

One of the earliest procedures that was commonly undertaken was surgery to correct something that was far more common in this time period than it is today - the “saddle nose.” This was a deformity that arose from collapse of the bridge of the nose, caused by trauma or most often syphilis. Its association with syphilis meant that for patients who suffered from a saddle nose, regardless of the cause, it was often assumed they had a depressed nose secondary to contracting the disease. Therefore, the surgeons and clinicians who were able to treat this could make a massive impact on their patients’ social lives.

Early attempts to correct this feature used paraffin, and we have written about what disastrous effects paraffin injections could have! Initially thought to be an inert substance, years down the line the paraffin could migrate or cause “paraffinomas,” essentially migrating tumours.

While clinicians quickly moved away from its use, lay injectors continued to use the substance with impunity, causing many clinicians to lead public safety campaigns. One clinicians, Dr. Seymour Oppenheimer of New York, wrote that paraffin injections, while "dangerous even in the hands of the well-equipped surgeon," were "doubly more dangerous ... at the hands of the ignorant, unscrupulous and uneducated `beauty doctor.’ ”

In other words, several doctors of the day were identifying a need and, indeed, a great appetite for cosmetic treatment among the public for a multitude of reasons. However, they were concerned that if their fellow clinicians did not step in and ensure that these procedures were done properly and ethically, there were plenty who saw the financial benefits in stepping in to try their hand on the unsuspecting public.

A Very Modern Debate

Reading about these ongoing debates highlights an interesting fact - that a hundred years ago clinicians were already discussing the value and cost of cosmetic treatments.

Historian Elizabeth Haikin wrote: “Moreover, surgeons' desire to differentiate themselves, as responsible, reputable members of the medical profession, from the so-called quacks on the profession's fringes, and their commitment to educating the public about this difference, suggest that they were watching with interest not only their colleagues' moves toward specialization but also the impressive growth of the American beauty business.”

There was also a shift in attitude at this time - that access to beauty and cosmetic treatments was consistent with notions of equality and self-improvement. That all women, regardless of the origins of their births, should be able to achieve whatsoever they desired in their physical appearance. We covered these concepts extensively in our article on the wonderful Madame Noel, the first female cosmetic surgeon and staunch feminist.

The issue of non-medical practitioners did create a dark side to the seeming increase in access to beauty treatments. When women were taken advantage of by the many non-medical quacks that abounded - and large amounts of money were lost when they could ill afford it - they were often unable to recoup their losses. In the UK, women who went to the police courts for try get refunds were dismissed by magistrates who claimed they should have known better, and felt they were vain silly women who had been burned by their own vanity. This only led to increase the stigma and trivialisation of the specialty.

The Lancet, the famous medical journal, wrote about its concerns with the situation in the early 20th century. criticising the lack of response from the courts: “To obtain £20 from a credulous lady’s maid and to inflict pain and injury upon her in addition to robbing her are at least…deserving of punishment.”

Final Thoughts

It’s clear from this brief sketch of the landscape of cosmetic medicine in the early 20th century that the same ethical questions and concerns we are preoccupied with today were already being discussed. It is equally fascinating and concerning that the UK today resembles the completely lawless nature of medical practice in the early 20th century. We certainly owe it to our patients to have learned from history, rather than repeat it.

Read our slide summary: “Who were the Beauty Doctors?” below.

References

Clark, J. “Clever ministrations”: regenerative beauty at the fin de siècle. Palgrave Commun 3, 47 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-017-0029-9

Haikin, Elizabeth. 1997. Venus Envy: The History of Cosmetic Surgery. The Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN: 0-8018-5763-5

Miller, C.C., 1924. Cosmetic surgery: the correction of featural imperfections. Davis.

Rogers B. O. (1971). A chronologic history of cosmetic surgery. Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine, 47(3), 265–302.

In 1933, a shocking exhibit toured America, displaying products that had blinded women, caused permanent hair loss, and even killed unsuspecting consumers. The "American Chamber of Horrors," as it came to be known, featured genuinely toxic cosmetic products, that contrast sharply with how remarkably safe modern products actually are.

Yet somehow, in our era cosmetic safety and regulation, we've developed an irrational fear of "chemicals" and "toxins" in beauty products. The irony is striking: we've never been safer from cosmetic harm, yet we've never been more frightened of our makeup bags.

Let's explore how the real horrors of unregulated cosmetics led to the robust safety framework we have today - and why most modern "clean beauty" fears fundamentally misunderstand how cosmetic regulation actually works.