The Dark Origins of Retin-A: How Prison Experiments Led to Modern Anti-Ageing Treatment

Some of the most groundbreaking discoveries in medicine happen completely by accident. From penicillin to X-rays, chance has shaped modern healthcare in ways we could never have planned. But perhaps no accidental discovery has had quite the same impact on dermatology and aesthetics as the revelation that a powerful acne treatment could turn back the clock on ageing skin.

Let explore the story of how tretinoin - also known as Retin-A - went from being a treatment for severe acne to becoming the gold standard in anti-ageing skincare. Because, as we shall see, behind this revolutionary treatment lies one of dermatology's darkest chapters.

The Man Behind the Discovery

Dr Albert Kligman

Dr. Albert Montgomery Kligman (1916-2010) was an American dermatologist born into a poor Russian immigrant family in Philadelphia in the early 20th century. Dr. Kligman co-invented Retin-A with Dr. James Fulton and Dr. Gerd Plewig, and was known for bringing scientific rigour to dermatology at a time when the field was lacking evidence-based approaches. He was also the first dermatologist to elucidate a correlation between sun exposure and the development of wrinkles, coining the term "photoaging!” Given these impressive accolades, you might think that he would be a celebrated figure in modern medicine - but that is far from the case.

Dr. Kligman's research methods, particularly his work at Holmesburg Prison from 1951-1974, have since been widely condemned as unethical and represent a dark chapter in medical research history.

The Problem That Started It All: Acne

Before we get into Kligman’s prison experiments, let’s take a step back and examine what was happening acne treatment at the time. In the late 1960s, severe acne was devastating the lives of countless patients, particularly teenagers, and the available treatments were limited and often ineffective. Traditional approaches like topical antibiotics and harsh scrubs could only do so much.

Kligman had been studying acidic Vitamin A, known as tretinoin or retinoic acid, for its potential in treating skin conditions. Previous studies in Europe showed that retinoic acid greatly damaged the skin, however these results did not diminish Kligman's interest in this acid.

After observing that retinoic acid cured keratonic disorders by removing the top layer of skin, Kligman theorised that retinoic acid could possibly combat acne. Kligman's search for effective acne treatments would soon lead him down a dark path.

The Holmesburg Experiments: A Dark Chapter in Medical History

Dr. Kligman's work at Holmesburg Prison began in 1951 when he was initially contacted to help treat an outbreak of athlete's foot. However, he quickly saw the potential of the prison as what he described as "a limitless supply of test subjects." The unique design of the prison contributed to making it an ideal environment for conducting experiments.

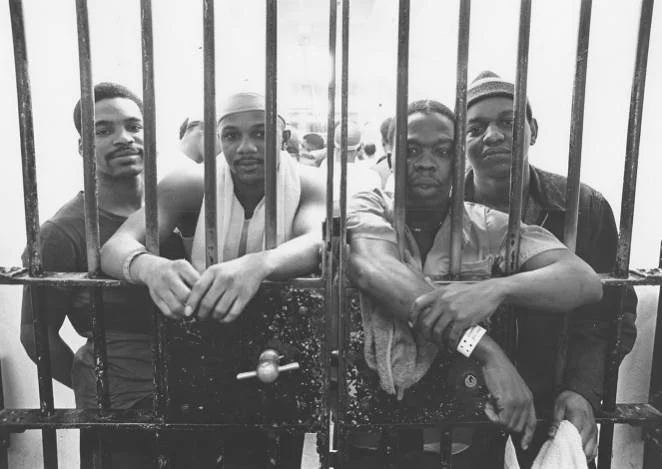

The scope of these experiments was horrifying and extensive. The subjects, who were predominantly male and of African American ethnicity, were offered $30-50 for participation in experiments that violated the Nuremberg Code of medical ethics. Some experiments included taking adhesive tape and applying it to an inmate's back, then ripping it off repeatedly until the skin became raw. Various chemicals were applied to inmates' backs, which were then covered with plaster, subsequently leading to blistering, chemical burns and severe cutaneous drug eruptions.

Temple University Libraries, Special Collections Research Center

Dr. Kligman performed experiments using detergents, soaps, radioactive and hallucinogenic compounds, and infected subjects with herpes simplex virus, vaccinia, human papillomavirus, and candida. Most disturbingly, he infected children with intellectual disabilities with fungal infections. Between 1951 and 1974, Kligman exposed approximately seventy-five prisoners to high doses of dioxin, the contaminant responsible for Agent Orange's toxicity to humans, with Dow Chemical paying Kligman $10,000 to conduct these experiments.

It was during these unethical experiments that Kligman began testing vitamin A derivatives for their anti-ageing and pigmentary effects, applying the derivative in varying doses and formulations on the skin of inmates. In a 1966 interview with the Philadelphia Inquirer, referring to the prison, Kligman was quoted saying "All I saw before me were acres of skin. I was like a farmer seeing a fertile field for the first time."

After a book on the Holmesburg experiments was published in 2000, several former prisoners attempted to sue Dr. Kligman and the University of Pennsylvania for intent to harm. The lawsuit was dismissed under the statute of limitations. However, the legacy of these unethical practices continues to resonate - in 2022, the City of Philadelphia issued a formal apology for the Holmesburg experiments, acknowledging the harm done to the predominantly African American inmates who were subjected to these procedures.

The Unexpected Side Effect

Long before this ethical reckoning, however, tretinoin had already made its way into mainstream medicine. Following FDA approval for acne treatment in 1971, something remarkable began happening among patients that would transform dermatology.

Patients using it to treat acne reported noticing a general improvement in the condition of their skin. These patients weren't just seeing improvements in their acne - they were mentioning something else entirely: their fine lines were disappearing, wrinkles were softening, and their skin texture was becoming smoother.

Considering this, Kligman and colleagues began trials to study the use of topical tretinoin in treating photodamaged skin. Beneficial results were subsequently verified by large multicenter trials and clinical experience supporting the efficacy and safety of topical tretinoin to treat photodamaged skin. (For more of the science behind retinoids, read our article here).

The formal recognition of tretinoin's anti-ageing properties took time. In 1995, topical tretinoin was approved by the FDA for the palliation of fine wrinkles, mottled hyperpigmentation, and tactile roughness of facial photodamage.

This marked a turning point in how we approach skincare. For the first time in history, there was a topical treatment with solid scientific evidence behind its anti-ageing claims. Today, retinoids remain the gold standard in anti-ageing skincare, with decades of research supporting their efficacy.

Final Thoughts

The story of tretinoin confronts us with an uncomfortable reality: one of dermatology's most transformative treatments was born from systematic human rights violations. Every tube of tretinoin, every prescription written, carries within it the suffering of predominantly African American prisoners who were treated as "acres of skin" rather than human beings deserving of dignity and protection.

The regulatory changes that followed Kligman's research - informed consent protocols, ethics committees, and prisoner protections - represent important progress in safeguarding human subjects. Today's rigorous ethical standards in medical research exist precisely because of past abuses like those at Holmesburg Prison.

While the accidental discovery of tretinoin's anti-ageing properties fundamentally changed how we think about skincare, we cannot separate this scientific triumph from its dark origins. Every time we benefit from these treatments, we carry a responsibility to ensure that medical research never again treats any human being as Dr. Kligman treated the prisoners of Holmesburg - as nothing more than experimental material for scientific advancement.

References

Kligman, A. M., & Fulton Jr, J. E. (1969). Topical tretinoin for acne vulgaris. Archives of Dermatology, 99(4), 469-476.

Rafal, E. S., Griffiths, C. E., Ditre, C. M., Finkel, L. J., Hamilton, T. A., Ellis, C. N., & Voorhees, J. J. (1992). Topical tretinoin (retinoic acid) treatment for liver spots associated with photodamage. New England Journal of Medicine, 326(6), 368-374.

Mukherjee, S., Date, A., Patravale, V., Korting, H. C., Roeder, A., & Weindl, G. (2006). Retinoids in the treatment of skin aging: an overview of clinical efficacy and safety. Clinical Interventions in Aging, 1(4), 327-348.

Casale J, Taylor A, Crane J. Albert M. Kligman, MD (1916-2010): A Controversial Genius in the Field of Dermatology. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2023 Jan;16(1):13. PMID: 36743970; PMCID: PMC9891217.

Melissa Crous, Nicholas Stefanovic, Laoise Griffin, HX21 Scars of confinement: the dark history of tretinoin, British Journal of Dermatology, Volume 193, Issue Supplement_1, July 2025, ljaf085.484, https://doi.org/10.1093/bjd/ljaf085.484

In 1933, a shocking exhibit toured America, displaying products that had blinded women, caused permanent hair loss, and even killed unsuspecting consumers. The "American Chamber of Horrors," as it came to be known, featured genuinely toxic cosmetic products, that contrast sharply with how remarkably safe modern products actually are.

Yet somehow, in our era cosmetic safety and regulation, we've developed an irrational fear of "chemicals" and "toxins" in beauty products. The irony is striking: we've never been safer from cosmetic harm, yet we've never been more frightened of our makeup bags.

Let's explore how the real horrors of unregulated cosmetics led to the robust safety framework we have today - and why most modern "clean beauty" fears fundamentally misunderstand how cosmetic regulation actually works.